Just as Diana Garcia was about to become a nurse, the world started shutting down due to the coronavirus.

First, her preceptorship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles was canceled.

Next, the exit exam she needed to graduate from West Coast University’s nursing program was canceled.

Then, her phone rang.

Taking flight

Garcia first realized she wanted to be a nurse while serving in the U.S. Air Force.

Enlisting at age 20, Garcia was an active-duty medical technician for six years, including two tours in Afghanistan. In 2013, she worked at Camp Leatherneck, helping soldiers at the U.S. Marine base get flight-ready for medical evacuation to Germany. In 2016, she was stationed in Bagram and worked at the hospital’s intensive care unit, where patients ranged from blast victims to the critically ill.

Garcia said the nurses she encountered in the military always impressed her with their knowledge and training, and by how willing they were to teach and “take the medics under their wings.”

“We worked as a team with them. They oversaw everything we did but our scope of practice as medics was very broad,” she said. “They taught us to work with minimal equipment. We not only learned to work in a hospital but we also learned to adapt in the field.”

Garcia loved how military nurses improvised and their decisive nature, like when her unit’s only option for a patient was to use a dialysis machine no one knew how to operate. The solution: Find a phone book.

“They were on the phone for like 12 hours with the manufacturer,” she said, “and they figured it out to save this guy’s kidneys.”

With her team’s encouragement, Garcia earned her vocational nursing license while in the Air Force but eventually she decided to switch to reserve status and go back to school full-time to become a registered nurse.

Duty calls

With the help of the GI Bill®, Garcia enrolled in the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at WCU-Los Angeles in 2017. She was just weeks from graduation when the pandemic hit the U.S.

In the middle of everything shutting down, Garcia was notified by her Reserve unit that she was being activated: “Be ready to go in three days. We can’t tell you where you’re going, but come to a meeting on base and we’ll give you all the info.”

“Of course, I thought, ‘Noooo! I’m not done with school yet. Let me see if I can figure something out.’ And they just told me, ‘We need a team now,’” she said. “So you just make it work.”

After an emergency meeting with WCU-LA nursing faculty, Garcia was relieved to hear her pre-licensure quiz could be postponed, and the exit exam requirements were being modified due to the pandemic. But once Garcia learned she was leaving for New York City to help with the COVID-19 crisis, she resolved to complete everything as quickly as she could.

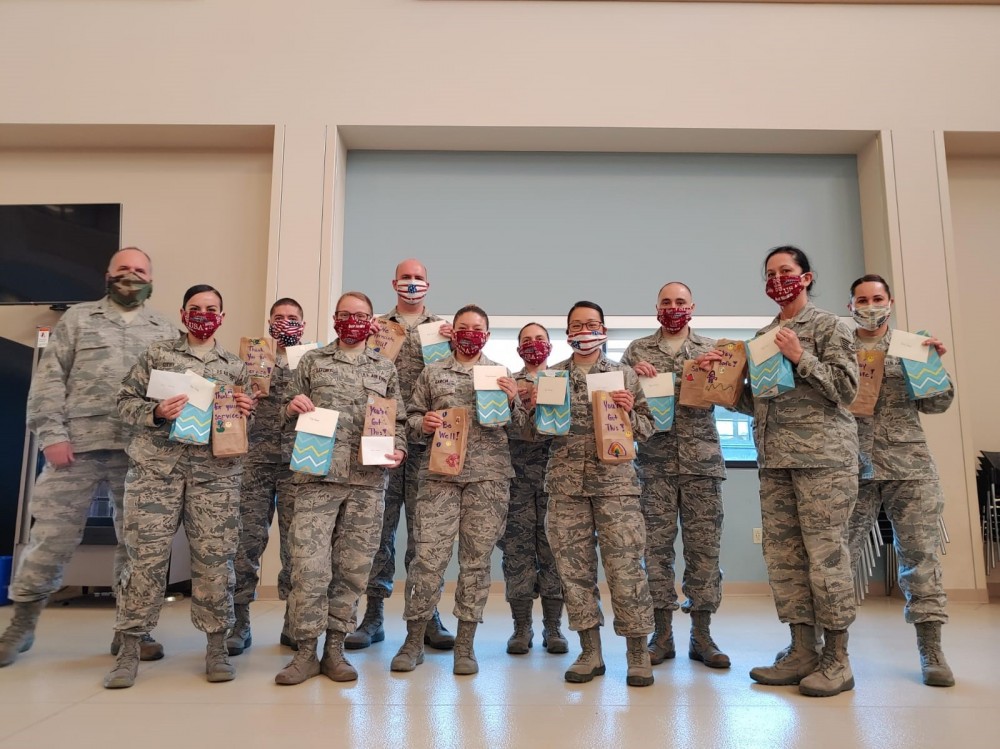

“I was in a team of 10 and everyone I was going with was super awesome so I just figured if I have a computer, if I have some days off, I’m going to finish as soon as possible,” she said.

Instead of packing for her deployment, Garcia spent most of her time preparing for the practice exam — a process that can take up to three months but is usually completed in four to six weeks. Garcia did it in 19 days.

“I did it almost all day and just gave myself very little time to pack,” she said. “I was very close to being done before I left.”

Within a week of landing in New York, Garcia had not only powered through her remaining practice modules but also studied for and passed her exit exam in-between shifts. Now, the only thing standing between Garcia and becoming a nurse was passing one final examination — and, of course, a potential six-month deployment to a COVID-19 hotspot.

“My commander told me that she would do whatever she had to do in order to get me to test while I was there, so that also made me feel a lot better,” Garcia said. “I didn’t want to keep putting that on hold.”

‘You’re going to New York’

Garcia said she had watched a lot of news leading up to her deployment but nothing could prepare her for being in the pandemic’s epicenter.

Her unit’s first assignment was at the Javits Center, an 840,000-square-foot convention center in Manhattan that had been converted into an Army field hospital.

“It was scary when they said ‘You’re going to New York’ and sure enough, the first day that we got there, Times Square, not a single soul was outside,” Garcia said. “I’ve been there when it’s normal New York, in 2010, and I could not believe my eyes to see that it was a ghost town in Times Square, in New York City.”

Because all the patients at the Javits Center were recovering from COVID-19 or coronavirus-positive, the Army hazmat teams had set up an elaborate “donning and doffing station” for personal protective equipment.

“We would sanitize in-between everything — you put on your gown, you sanitize; you put on your gloves, you sanitize; you put on your mask, you sanitize,” Garcia said. “That technique led to zero members getting COVID there, so I thought that was really incredible.”

Garcia’s unit arrived as the final patients were being discharged from the 2,500-bed facility, which had treated more than 1,000 New Yorkers in a month. After taking over from the Army for a few days, the medical center closed and the members of Garcia’s unit were transferred to various community hospitals across the five boroughs.

‘War zone’

Even though her team arrived after the crush of COVID-19 cases, Garcia said it was obvious the hospital staff where she was sent in Queens was happy to have reinforcements. With a population of over 2 million, the Queens borough was one of the hardest-hit areas in the city, with more than 60,000 confirmed coronavirus cases, and over 6,000 deaths since the outbreak.

“You could just see the relief that they had additional hands and that made us feel really good because we knew they were tired,” Garcia said. “We even had some military nurses that had been there during the really rough times and they were very relieved to have more help.”

As a medic, Garcia did supportive care for the patients and assisted hospital staff in the ICU, while dressed in full PPE. What struck her was how profoundly sick the COVID-19 patients were, the amount of attention they required, and how there were no loved ones at bedside due to the quarantine.

“Nurses can really make a difference. I respect all of these travel nurses so much because they volunteered for this and they don’t have a military background. This was very similar to a war zone to me because you are putting yourself at risk of becoming sick.”

— Diana Garcia, WCU-LA BSN Alumni

“It was just very different not having family around. When I worked at David Grant Medical Center (at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California) you always had family there,” she said. “To see these patients, a social worker would come in and FaceTime with the family even though the patient was on a vent. They could still hear so that was really tough, just knowing that these people couldn’t have their family.”

But just like in Afghanistan, Garcia said, the nurses she worked alongside in Queens both inspired and educated her.

A top-secret mission

On her days off, Garcia would study to take the National Council Licensure Examination — or NCLEX — the nationwide exam for the licensing of nurses in the United States and Canada. Even while working, Garcia said some of the ICU nurses in Queens would quiz her during any downtime between patients.

“I would read the questions out loud and they would ask me, ‘Well, which one would you choose? What are the side effects of this drug?’ Then they would explain to me the rationale behind the different options available,” Garcia said. “I was studying while working so that was really cool. I feel it definitely gave me a boost in my confidence.”

“I didn’t tell anyone. Only my commander and my coworker, but no one else. I was like ‘That’s it. I don’t want anyone to ask me about it and I don’t want to be stressed,’” she said. “So, I went and I took my test.”

Less than 48 hours later, Garcia learned she had passed.

Word soon got back to Garcia’s unit and a small, surprise celebration dinner was organized. They even got her a cake.

“That was really nice because that was a moment I thought I was going to share with my family. Even though I was really excited, I was also bummed out, but one thing I have learned in the military is your team becomes your family away From home. I’ve spent many birthdays away home, spent many holidays but the people I’m with always make up for being away From my family,” Garcia said. “I don’t even know how I did it but I’m glad I did. It was probably one of the proudest moments in my life because everyone was like ‘you took your test out here in New York City during a pandemic. That’s insane.’”

The journey home

Garcia’s deployment to New York City ended after five weeks. Prior to leaving, everyone on her military flight was tested for coronavirus via nasal swab. Once back in California, Garcia self-isolated for an additional 14 days and then was tested again for coronavirus on the 15th day.

Now a full-fledged RN, Garcia spent her time in quarantine by applying to new grad programs in the area, specifically in pediatrics. She also plans on seeking a commission in the Air Force, and wants to become an officer in its medical corps. But, in the meantime, she still has some work to do as an enlisted airman in the Reserves.

“Right now, I’m working on a presentation for our base commander and our general. She told us everyone wants to hear what we did so she asked us to put a little slideshow together,” Garcia said. “She said this never happened before so this is the way that we’re going to learn in the future and prepare all of our medics for another event like this.”

Lessons learned

If the pandemic taught Garcia anything, it was you have to be flexible to be a nurse — flexible in how you approach problems, flexible in how you deal with people, and flexible in your belief that you can fix everything and everyone.

“We’re always taught to heal and to do everything you can for a patient, but there are going to be instances where you cannot. As a nurse you just have to ground yourself and do what’s best for the patient,” she said.

Garcia said she watched healthcare staff push themselves mentally and physically to the limit during her deployment, and was glad to see that the public seemed to recognize how demanding the job could be.

“This wasn’t the first time nurses had seen patients die every day. It’s the first time that others had seen it because there were hundreds and hundreds of people dying, but that’s the day-to-day life of the nurse — you’re taking care of patients and you can do everything in your power but sometimes they just don’t make it. It’s a very hard job and I’m very proud to be a part of that culture because I’ve worked with a lot of amazing healthcare workers, and to see all the things they were able to do during a time like this, is very inspiring.”

WCU provides career guidance and assistance but cannot guarantee employment. The views and opinions expressed are those of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs or position of the school or of any instructor or student.